Ludwig Roselius explored the question of the origins of humankind in ever greater depth during the 1920s. In this, he was greatly influenced by the controversial theories of Herman Wirth, a scholar of prehistory and early history. Wirth placed the sunken island of Atlantis in the North Atlantic, believing it to be inhabited by Germanic people, who then fled south before the Ice Age, bringing the light of culture to Greece and Egypt.On the history and origin of this theory: Arn Strohmeyer: Mythos Atlantis, Bremen 1992, here p. 32ff. This implied that the Germanic culture was the oldest; as Roselius repeatedly put it: the belief should be ‘ex occidente lux’Adopting Wirth’s theories, Roselius gives an account of his view of the history of humankind in his writings about Böttcherstrasse to the Führer: Ludwig Roselius: Die Vollendung der Böttcherstrasse, in: Albert Theile (ed.): Die Böttcherstrasse in Bremen, Idee und Gestaltung, Bremen 1930 (Schriften zur Böttcherstrasse 1 in Angelsachsen Verlag), p. 44-52, esp. p. 48-52 (light from the West), not ‘ex oriente lux’ (light from the East).(Roselius can be heard explaining his theory here (German audio only).Ludwig Roselius during a tour of Böttcherstrasse, in: Die Böttcherstraße in Bremen – Eine Straße der Wandlungen in Mikrophon, first broadcast 16 June 1932 by Norag and Deutschlandsender; published as audio CD by Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt/Potsdam and die Böttcherstraße GmbH 2001, here: CD 1, Track 4 Roselius House – Ludwig Roselius on his collection 5‘50‘‘ to 6‘31‘‘ (German only).

The intention of Roselius and his architect Bernhard Hoetger was, through their symbol-laden architecture, to elevate this view of human history into the realm of the quasi-religious and give it a futuristic quality. They also simply wanted their architecture to cause a sensation, which it did.Dozens of newspaper articles from all corners of the world with reports on Atlantis House have survived in the archive’s collection of newspaper cuttings. In Bremen, the project was mostly the subject of harsh criticism or ridicule. Built out of an unusual combination of materials – glass, timber, reinforced concrete – in geometric forms between 1929 and 1931 with art deco interior design, the inside of Atlantis House was not at all ideological in nature. Rather, Roselius made the functional rooms – auditorium, reading room, assembly hall and club rooms – available to the ‘Club zu Bremen’, which he co-founded, as its home.

- to Greece and Egypt.On the history and origin of this theory: Arn Strohmeyer: Mythos Atlantis, Bremen 1992, here p. 32ff.

- ‘ex occidente lux’Adopting Wirth’s theories, Roselius gives an account of his view of the history of humankind in his writings about Böttcherstrasse to the Führer: Ludwig Roselius: Die Vollendung der Böttcherstrasse, in: Albert Theile (ed.): Die Böttcherstrasse in Bremen, Idee und Gestaltung, Bremen 1930 (Schriften zur Böttcherstrasse 1 in Angelsachsen Verlag), p. 44-52, esp. p. 48-52

- (German audio only).Ludwig Roselius during a tour of Böttcherstrasse, in: Die Böttcherstraße in Bremen – Eine Straße der Wandlungen in Mikrophon, first broadcast 16 June 1932 by Norag and Deutschlandsender; published as audio CD by Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt/Potsdam and die Böttcherstraße GmbH 2001, here: CD 1, Track 4 Roselius House – Ludwig Roselius on his collection 5‘50‘‘ to 6‘31‘‘ (German only).

- which it did.Dozens of newspaper articles from all corners of the world with reports on Atlantis House have survived in the archive’s collection of newspaper cuttings. In Bremen, the project was mostly the subject of harsh criticism or ridicule.

The façade (Fig. 2) of the building, on the other hand, told of the cult of Germanic values: rather than the brick that dominated the street, Hoetger used steel, glass, timber and exposed concrete to construct a geometric-modular façade. It seems almost futuristic in comparison with the quaint amorphous structure of Paula Becker-Modersohn House. Between the horizontal ribbon windows, Hoetger created wooden parapet panelling (Fig. 3) with the Germanic names of the months in the form of abstract reliefs. The highlight, keeping watch over the entrance, was the ‘Tree of Life’ (Fig. 4) – an enormous wooden sculpture projecting beyond the façade depicting the Nordic powers of fate and a crucified figure in a sun cross, which the viewer could take to be Christ at first glance. However, the quote in rune-like writing around the perimeter of the sun cross comes from the Nordic Poetic Edda and says that the figure is a pagan hero who is making a self-sacrifice to Odin.“I know that I hung on that windy tree, spear-wounded, nine full nights, given to Odin, myself to myself.” Hildegard Roselius interprets the crucified figure as follows: “The ‘Tree of Life’ on Atlantis House is not a Christian symbol. It represents the idea of self-sacrifice for a grand idea that is latent or inherent in all religions. Taken from an old Germanic myth, it harks back to the very beginnings of our people, expressing their hopes for a new day to dawn after the endless winter nights of the Ice Age… It creates a visual link between, on the one hand, an old myth according to which the Germanic kings are said to have sacrificed themselves for their people in desperate times by crucifixion and, on the other hand, the cosmic myth of Odin, whose death each summer solstice is essential to life each new cycle of the year,” quoted by Ernst Müller-Scheessel in: Das Robinson-Crusoe-Haus und das Atlantis-Haus in der Böttcherstrasse zu Bremen, in: Niedersachsen, October 1931 issue, p. 440

Stepping through the ‘roots’ of the ‘Tree of Life’ brings visitors into Hoetger’s highly geometric stairwell, which, bar the lighting control, has survived in its entirety to this day. A reinforced concrete spindle with round glass blocks is suspended on three slim triangular columns and only connected to the wall at the entrances to the floors (Fig.5); a technical masterstroke that attracted a lot of attention in the field at the time.Deutsche Bauhütte, Hanover from 22 July 1931 and Beton und Eisen, Berlin, issue 17 from 5 September 1932, p. 261-263 The narrow columns down the centre of the spindle contain concealed strip lights that provide indirect lighting (Fig. 6) the height of the stairwell, guide visitors towards the light and end at the ‘Sky Room’, which has also survived almost intact. Unequalled in form and design either before or since, Hoetger’s ‘Sky Room’s’ (Fig.7) parabolic barrel vault consists entirely of glass blocks, girded by six steel beams ( Fig. 9) and held in place by reinforced concrete.

- to Odin.“I know that I hung on that windy tree, spear-wounded, nine full nights, given to Odin, myself to myself.” Hildegard Roselius interprets the crucified figure as follows: “The ‘Tree of Life’ on Atlantis House is not a Christian symbol. It represents the idea of self-sacrifice for a grand idea that is latent or inherent in all religions. Taken from an old Germanic myth, it harks back to the very beginnings of our people, expressing their hopes for a new day to dawn after the endless winter nights of the Ice Age… It creates a visual link between, on the one hand, an old myth according to which the Germanic kings are said to have sacrificed themselves for their people in desperate times by crucifixion and, on the other hand, the cosmic myth of Odin, whose death each summer solstice is essential to life each new cycle of the year,” quoted by Ernst Müller-Scheessel in: Das Robinson-Crusoe-Haus und das Atlantis-Haus in der Böttcherstrasse zu Bremen, in: Niedersachsen, October 1931 issue, p. 440

- that attracted a lot of attention in the field at the time.Deutsche Bauhütte, Hanover from 22 July 1931 and Beton und Eisen, Berlin, issue 17 from 5 September 1932, p. 261-263

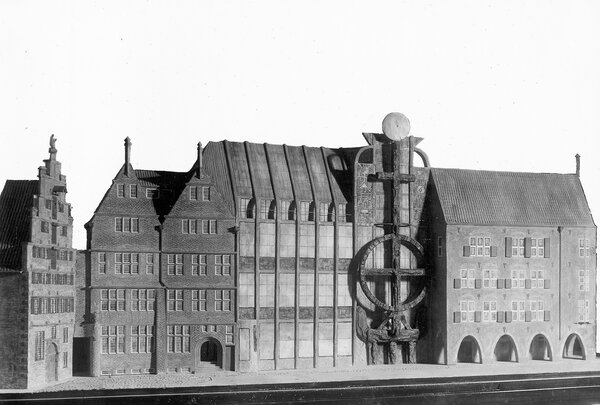

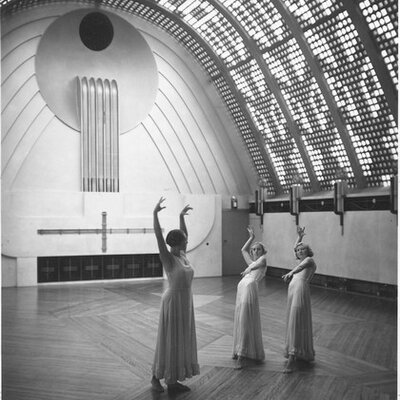

Originally, the vault was going to consist of two flat expanses of glass blocks, which met at an acute angle at the apex, according to a construction model Hoetger had made. (Fig. 8)Be it for technical or aesthetic reasons , this ceiling form was scrapped. Hoetger designed the vault in the unusual shape of a parabola, perhaps inspired by the parabolic arcades of the Kontorhaus from 1927 by Runge & Scotland, which was built by that time. The model was made by Rudolf Gangloff based on sketches by Bernhard Hoetger. (Gangloff’s invoice 5 October 1929, Böttcherstrasse archive, 1.2.1. Atlantis box) Hoetger rendered the north wall of the room with geometric, large-scale abstract reliefs that, with a cross of light and parabolic dish, are reminiscent of an altar-like arrangement and give the entire room a sacred impression. White and blue glass blocks resemble the pattern of a tree tapering off the higher it goes. On the south end hangs (Fig. 12) a slightly concave, golden metal disc that is also presumed to be a sun disc.Das Haus Atlantis und das Robinson-Haus, in: “Der Frosch”- Bulletins from the Bremer-Schwimm-Club von 1885 e.V. issue 7 July 1931, p.4 When it was dark, it was possible to project this disc onto the parabolic dish on the north wall with a spotlight.Described thus in: Das Atlantishaus von innen – Bremens neue Sehenswürdigkeit, in: Bremer Volkszeitung, 17 July 1931, first supplement of No. 164: “…in the evening a spotlight shines on a large golden disc which then suffuses the entire room with a matt gold radiance. This gentle radiance trickles down from every golden projection, rising, on the narrow verticals in the centre of the background, to a glistening waterfall that appears to flood the room with its glow.” At this end, stairs led up to a gallery and into the domed room (Fig. 10) beyond over the stairwell. This room is circular with a slightly concave vaulted ceiling of glass blocks. Here the blocks are arranged in the shape of a cross. Glass blocks also dot the floor. Hoetger gave all the details such as lights and heating/ventilation grilles geometric designs. However, this room was not used for religious gatherings but initially as a gymnasiumGenerally described thus in the press reviews 1931/32 (Fig. 13) and, as of 1933, for exhibitions as well.

- according to a construction model Hoetger had made. (Fig. 8)Be it for technical or aesthetic reasons , this ceiling form was scrapped. Hoetger designed the vault in the unusual shape of a parabola, perhaps inspired by the parabolic arcades of the Kontorhaus from 1927 by Runge & Scotland, which was built by that time. The model was made by Rudolf Gangloff based on sketches by Bernhard Hoetger. (Gangloff’s invoice 5 October 1929, Böttcherstrasse archive, 1.2.1. Atlantis box)

- sun disc.Das Haus Atlantis und das Robinson-Haus, in: “Der Frosch”- Bulletins from the Bremer-Schwimm-Club von 1885 e.V. issue 7 July 1931, p.4

- on the north wall with a spotlight.Described thus in: Das Atlantishaus von innen – Bremens neue Sehenswürdigkeit, in: Bremer Volkszeitung, 17 July 1931, first supplement of No. 164: “…in the evening a spotlight shines on a large golden disc which then suffuses the entire room with a matt gold radiance. This gentle radiance trickles down from every golden projection, rising, on the narrow verticals in the centre of the background, to a glistening waterfall that appears to flood the room with its glow.”

- gymnasiumGenerally described thus in the press reviews 1931/32

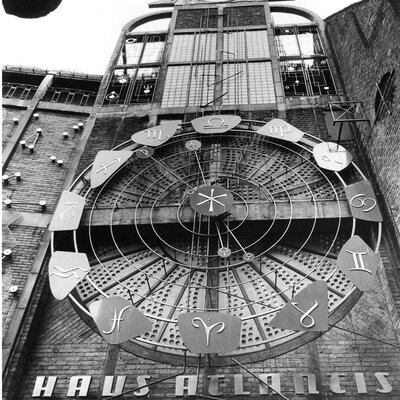

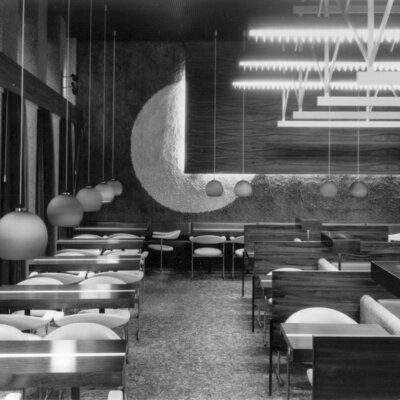

Atlantis House was the only building on Böttcherstrasse not to be substantially destroyed in the bombing on 7 October 1944. However, the expressive wooden figure and the panels depicting the months were burnt (Fig. 11). The façade was completely walled up to facilitate the new, modern uses of Böttcherstrasse for Atlantis light displays and chamber plays from 1946 onwards. Completed in 1954, a metal structure (Fig.14) of spotlights was fixed to this somewhat austere façade, which depicted the Northern skies. An astronomical clock (Fig. 15) with the signs of the zodiac throughout the year was put in place of the sun cross. Eventually, in 1965, the façade was completely redone in brick by Ewald Mataré, which reincorporates some of the pre-war elements.See the text The façade of Atlantis House after World War II in the Topics section Below the cinema and theatre, Bremen’s first vegetarian restaurant ‘Martini’ opened on the ground floor in 1952 in place of the Kaffee HAG confectionery, which was then modernised (Fig. 16) in 1964 by architects Uhde and Welp.

In 1988, Atlantis House was separated out of the Böttcherstrasse complex and sold to an investment group. A hotel was built on the site behind it, which connects to Atlantis House. There is still a restaurant on the ground floor but the cinema and theatre have been turned into meeting rooms. Only the staircase and ‘Sky Room’ were left unaltered, being under a protection order.

The ‘Topics’ section in the menu contains an analysis of where the House of ‚Mythbuilding‘ fits in in terms of politics and history, and how the façade was dealt with after 1945.

- which reincorporates some of the pre-war elements.See the text The façade of Atlantis House after World War II in the Topics section